Options for designing a public option

06.02.2020

NOTE: This blog was originally published in The RAND Blog on May 28, 2020.

State and federal policymakers are considering adding state-backed public options to the individual market in an effort to expand health coverage and improve affordability. Such options would be either publicly administered or privately administered using publicly-defined provider reimbursement rates. Earlier today, we released an analysis of what would happen if public options became available in the country’s health insurance exchanges (sometimes termed, “marketplaces”). This analysis used RAND’s COMPARE microsimulation model to gauge effects on coverage and cost. These scenarios included:

- A public option sold on the exchange, based on provider reimbursement between Medicare and private provider levels (“low reduction”).

- A public option sold on the exchange, based on provider reimbursement between Medicaid and private provider levels (“high reduction”).

- A public option sold only outside the exchange, based on the high payment reduction. Under this scenario, a state would need a waiver under section 1332 of the Affordable Care Act (“ACA”) to allow consumers who qualify for advance premium tax credits (“APTCs”) to use federal pass-through payments to buy the public option. Such payments would approximate each consumer’s APTC amount.

We analyzed a fully phased-in version of a public option in each scenario assuming nationwide implementation, using nationally representative data and economic theory to estimate effects on coverage, premiums, and federal spending. In this post we share some observations about the results of the modeling and key considerations for policymakers. We identify three important lessons:

- A public option could lower unsubsidized enrollees’ premiums, at minimal cost to the government. Further, a public option could reduce federal spending on APTCs without major changes to overall coverage levels.

- Policymakers could alleviate potential problems a public option might otherwise create for some enrollees who qualify for APTCs.

- Context matters. The same public-option approach could yield different outcomes in different states with different market environments.

To be sure, our analysis had limitations. First, our modeling preceded the COVID-19 pandemic. Our estimates thus do not reflect changes in enrollment and premiums resulting from the pandemic. Second, the modeling assumed that public options could, in fact, achieve specified provider reimbursement reductions. Some have expressed skepticism about the magnitude of reimbursement cuts that states could achieve – a skepticism that is likely to grow more pronounced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, the analysis estimated the proposed policies’ effects, without attempting to evaluate their likelihood of enactment. In particular, one of the scenarios assumed an off-exchange offering that would require a state to obtain a 1332 waiver, even though the current administration has made clear that it will not grant such waivers to support these kinds of state efforts. Nevertheless, we thought it was important to model this option, both because federal policies can change and because the scenario’s effects illustrate important broader points, as explained below.

A public option could lower premiums and reduce federal spending

A public option plan that reduces provider prices in the non-group market could lower the federal government’s health care spending. In each of the above-described scenarios, we assumed that public option plans could obtain lower provider prices and thereby charge lower premiums. We also assumed that competitive pressures would lead private insurers to reduce their premiums as well, through measures that might include better contracting. Finally, for the scenarios in which the public option was offered on-exchange, the public option was assumed to lower the premium for the second lowest-cost silver plan, often termed the “benchmark” plan. The combination of benchmark premium and household income determines the amount of each consumer’s APTC, which a consumer can use to buy any exchange plan.

In all scenarios, we found that public-option premiums were lower than individual market premiums under the status quo. Furthermore, we projected net federal savings on APTCs between $7 billion and $24 billion a year. The public option’s impact lowering benchmark premiums thus yielded federal fiscal gains.

The modeling also found that this public savings did not cause large overall changes in coverage. Some gained and others lost insurance under the various modeled approaches, but total coverage levels increased only slightly with a public option under most scenarios. In thinking about a public option, it is thus important for policymakers to distinguish between objectives that involve coverage levels, premium costs to consumers, and federal spending.

Certain public option designs could pose risks to some low- to moderate-income enrollees

One might think that lower premiums are great for all enrollees. However, lower premiums can increase costs for some consumers. As noted earlier, APTCs, which help finance 69% of all individual-market coverage, are based on the benchmark premium. If that falls, APTC beneficiaries enrolled in the benchmark plan would be unaffected because their cost to buy that plan is based entirely on income. However, APTC enrollees in plans that charge less than the benchmark could wind up paying more, since their APTC amounts would decline.

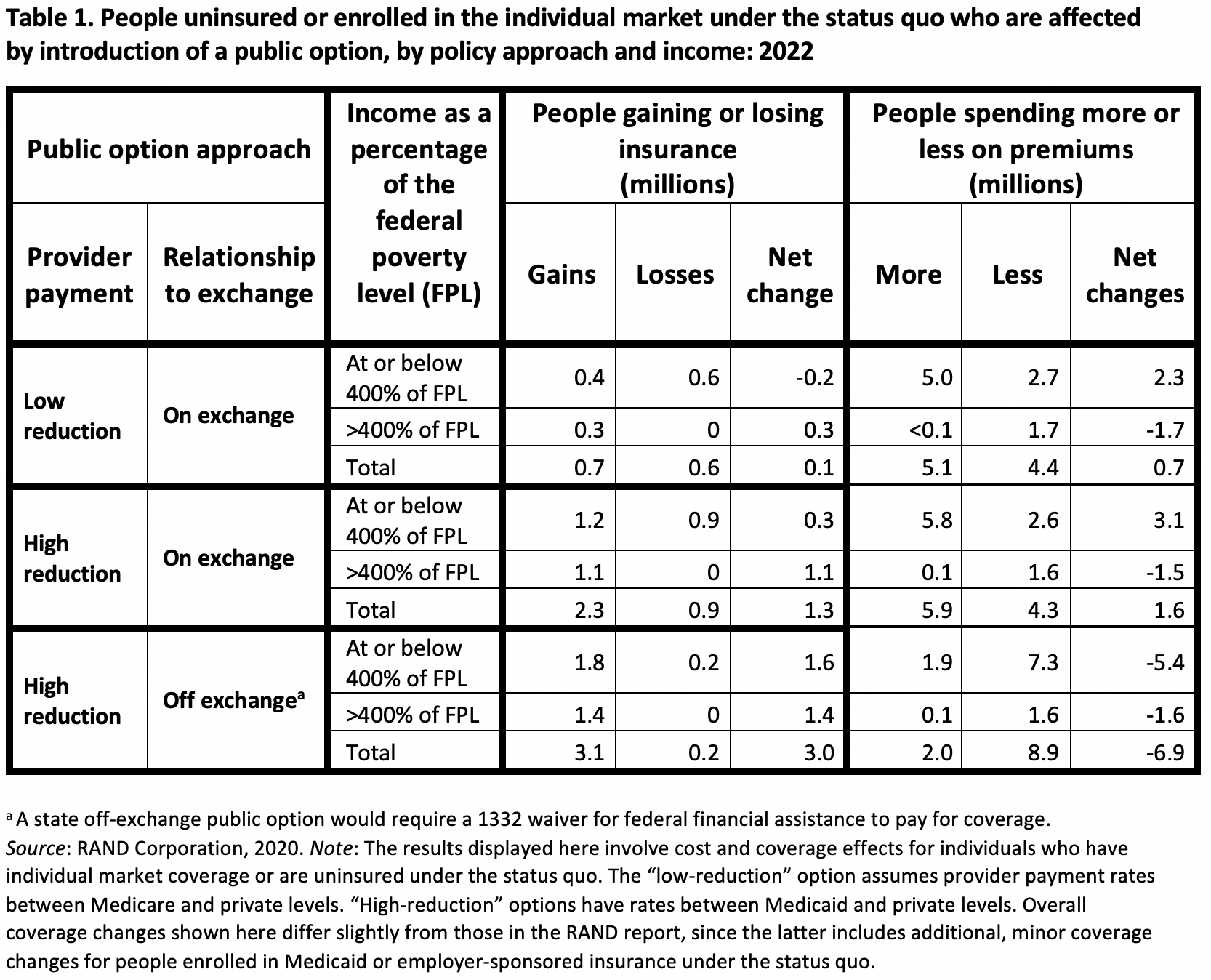

With regard to making a public option available in the exchange that would lower benchmark premiums, our microsimulation found that, while that policy approach would not result in major changes to the total number of uninsured, it would have implications for who obtains or loses coverage and who pays more or less in premiums (see Table 1).

- Some consumers with incomes at or below 400% of the federal poverty level (“FPL”) would lose coverage or pay more in premiums. That income threshold is the maximum amount a household can earn and still qualify for APTCs. Almost all consumers projected to lose insurance (0.6 or 0.9 million, under the low- and high-reduction scenarios, respectively) are in this income group. Because others with incomes below 400% of FPL would gain coverage, the total number with insurance in this income band would fall by 0.2 million or rise by 0.3 million, depending on the scenario. Those who pay more in premiums would outnumber those who pay less, but total premium payments for this income group would rise under the low-reduction scenario and slightly decline under the high- reduction scenario (Appendix 2 of the RAND report, results not shown here).

- Above 400% of FPL, almost all affected consumers would gain coverage or pay less in premiums. Depending on the size of the provider payment reduction, a nationwide on-exchange public option would increase coverage by 0.3 to 1.1 million people in this income group, without offsetting coverage losses. Many would spend less on premiums, while almost none would spend more.

A Public Option Can Be Designed to Increase Coverage and Lower Costs for Enrollees at All Income Levels

We also modeled the effects of a public option that was structured to limit the option’s impact on APTC amounts. In the high-reduction scenario that offered the public option only off-exchange, that option did not directly affect the benchmark premiums that determine APTC values. APTC-eligible enrollees could buy the public option off exchange, under this scenario, using federal pass-through payments that approximate APTCs. Our modeling results showed this policy would increase the total number of insured by 3 million, with gains distributed above and below 400% of the FPL. Premium savings for the already insured would likewise be shared across both income groups.

These results involve three specific policy examples, but they illustrate an important broader point. By combining a public option with guardrails that limit APTC reductions, policymakers can help consumers across the income spectrum benefit from the public option’s premium savings. That combination is possible without a 1332 waiver. For example:

- A state exchange could limit low-cost, silver-tier public options to a single plan per county, using competitive bidding to select the sponsoring carrier, which could vary geographically. The exchange would then preserve APTC amounts by maintaining a minimum pricing distance between the public silver plan and all other silver qualified health plans (QHPs) sold on the exchange. As a second example, Maryland implemented reinsurance to lower premiums while limiting APTC reductions by encouraging carriers to price silver QHP premiums above gold premiums, reflecting the higher percentage of paid-claims in silver than in gold plans.

- Federal lawmakers adding a public option to all health insurance exchanges could shield APTC beneficiaries by making other changes to the ACA. For example, the public-option proposals advanced by some Presidential candidates have increased APTC amounts, offering a combination that could potentially enable significant net gains in affordability and coverage at all income levels.

Different Contexts Could Yield Different Outcomes

Our modeling estimated overall national results of various public-option policies, but states with different environments are likely to experience different effects from common policy approaches. Some state exchanges include Medicaid managed care organizations with significant QHP offerings, leaving less room to achieve provider savings by offering a public option with reduced provider reimbursement levels. Furthermore, provider finances vary. Different hospitals could be affected quite differently by the same overall reimbursement reduction. Those differences may become more pronounced as hospital finances become increasingly strained because of the COVID-19 disease.

Issuers currently in the individual market could react very differently to the introduction of a public option, depending on local conditions. Some private issuers could respond to a public option by lowering their premiums, perhaps renegotiating network contracts. Other issuers may exit markets or otherwise react negatively if, for example, they are unable to match the public option’s cuts to provider payments, or if the introduction of a public option changes the private insurers’ risk mix. The latter issue may be compounded by cuts to risk-adjustment transfer payments since such payments are based on average statewide premiums in the individual market, which are likely to decline with a public option.

Put simply, state context matters. A state’s issuers, their provider reimbursement levels, their competitive reactions to a new public option, and other characteristics of local providers will all influence the eventual effects of a public option policy.

Conclusion

A public option that lowers individual-market premiums based on publicly-administered prices could be a powerful tool to lower health care spending without dramatically reducing overall coverage levels. Unfortunately, if that tool is deployed without carefully considering the detailed structure of private insurance markets under the ACA, unintended and negative consequences could result, especially for low- and moderate-income consumers. Fortunately, policymakers can combine public options with APTC guardrails to improve affordability and coverage for a broad range of affected families, depending on key policy details and market conditions. We encourage officials to thoughtfully evaluate what approach best meets their state’s needs, taking into account local conditions and priorities.

Michael Cohen is a policy consultant at Wakely and previously served in CCIIO as policy and research staff.

Al Bingham is an actuarial consultant at NovaRest Actuarial Consulting and previously served as an actuarial consultant at Wakely and as senior actuary at CCIIO/CMS on ACA-related issues.

Stan Dorn directs the National Center for Coverage Innovation at the nonprofit, nonpartisan Families USA, where he also serves as senior fellow.

Jodi Liu is a policy researcher at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation.

Christine Eibner is the Paul O’Neill Alcoa Chair in Policy Analysis and a senior economist at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation.

The authors would like to thank the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, which provided the support that made our work possible.